The Microplastics Around and In Us

“People misunderstand how many microplastics are actually around us. You just don’t think about it. I try to use as little plastic as possible—that’s almost impossible. They’re everywhere.” — Nylah McClain

Section 1: The Domino Effect

To explain something complex, you have to start small—

very small .

The human body is composed of approximately 70% water. It's fluid courses through your blood, cells, tissues, and organs. Like our bodies, the planet is also about 70% water. In recent history, plastic pollution has been rising in global water sources. It's no surprise that plastics have now been found in the human body.

Created to mimic natural rubber, plastic has found itself in many items made for everyday use. Plastics now cover the world's consumers inside and out. It’s in packaging, clothing, cosmetics, water, food, and so much more.

The creator of this—Alexander Parkes, who first unveiled his creation of synthetic plastic in 1862. Could never have imagined that his invention would become one of the most quietly catastrophic forces in human history.

What are Microplastics? How do they form?

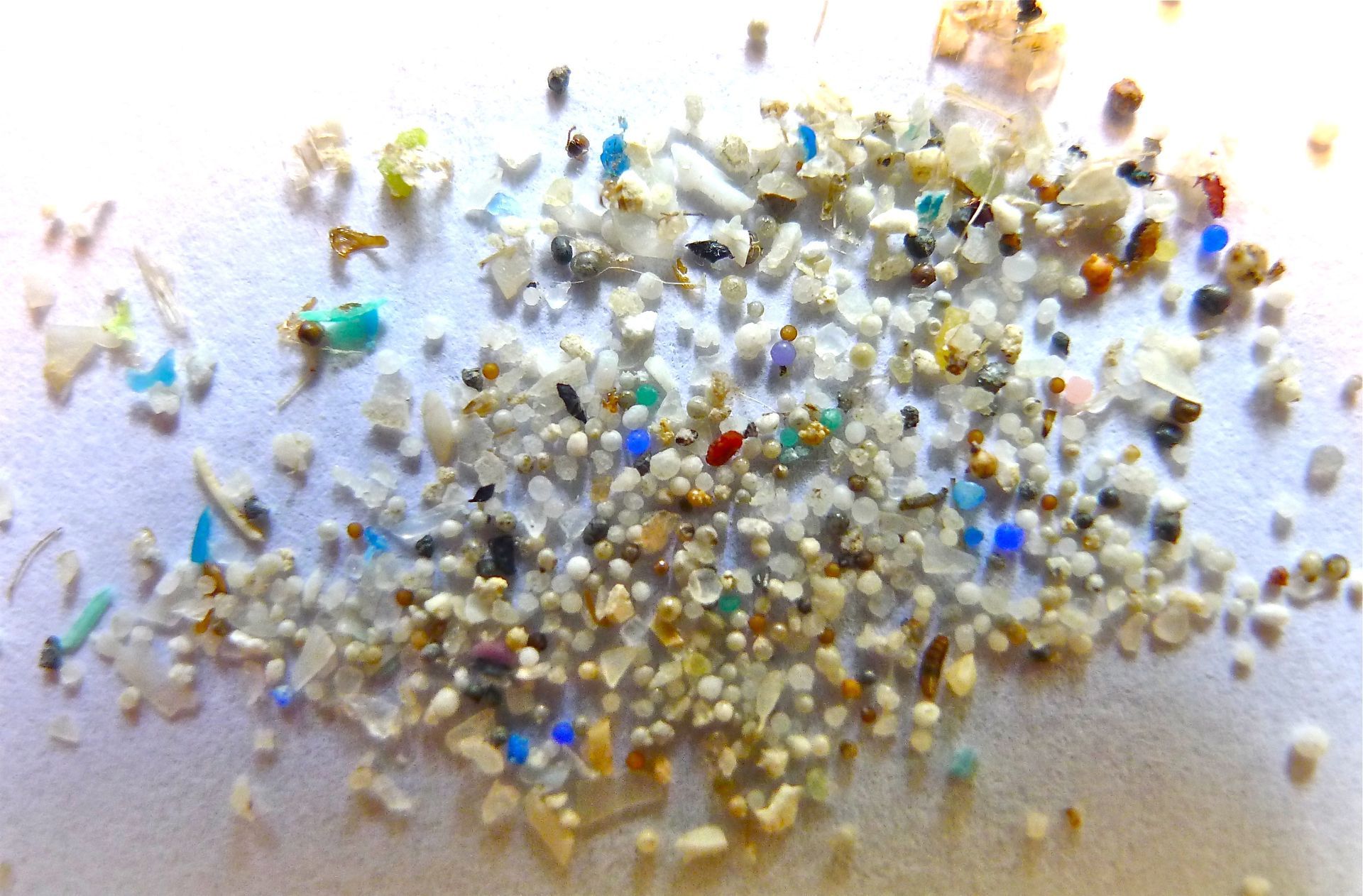

"Microplastic" by Oregon State University from Microplastics is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Plastics are synthetic materials made from petroleum. Over time, larger plastic objects like bottles, bags, and clothing break down through processes like fragmentation and fiber shedding. Fragmentation occurs when plastics break down due to exposure to sunlight, water, and friction. Fiber shedding happens as synthetic fabrics erode during use or washing. These breakdown processes produce tiny plastic particles, called microplastics, that pollute the environment. Specifically, microplastics are defined as particles smaller than 5 millimeters. They’re in the air, soil, your body, the water—everywhere. To drive it home, microplastics have been found in the following: kidney, liver, saliva, blood, placenta, table salt, produce, seafood, rain, cleaning products, cosmetics (makeup, face washes), clothes, dust, and trash.

Microplastics can be divided into two categories: primary and secondary. Primary microplastics are manufactured intentionally and are often used in exfoliating personal care products. Alternatives like pumice, oatmeal, or crushed walnut shells are natural and are also used. However, synthetic microbeads were once common in face washes and toothpaste until bans were introduced in some countries like Canada, France, Ireland, China, the United States, and New Zealand. In addition, primary microplastics such as Nurdles serve as raw material for creating basically all plastic products by being melted and molded. They're especially small pellets that are able to easily escape into the environment during the production and transportation of plastic goods, leading to pollution.

Secondary microplastics, on the other hand, are formed

unintentionally. They result from the breakdown of larger plastic items through chemical, physical, or biological processes. Sunlight exposure, friction, and microbial activity slowly reduce everyday plastics into minuscule fragments. Nylah McClain, a microplastic expert at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore researching the effects of secondary microplastics in blue crabs, explained in our interview that “A microplastic can still break down even further if the chemical bonds will allow that...plastics are hard to biodegrade because they’re manmade.”. This means that even after plastics become microplastics, they can continue to break down into smaller particles, making them almost impossible to remove from the environment. Whether created on purpose or as a consequence of plastic waste. Both types of microplastics now circulate through every layer of life, forming the first domino in a chain reaction with consequences we’re only beginning to understand.

How Do Microplastics Enter the Body?

Microplastics enter the body through two main ways: inhalation and ingestion. While other ways exist, more research is needed to better understand. Breathing in microplastics in the air or ingesting them through contaminated food and water allows these small particles to bypass our natural defense and integrate into our bodies.

What Chemicals Are Commonly Found in Microplastics?

Many microplastics contain toxic chemicals (additives) such as Bisphenol A (BPA) and Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). These are commonly known as “forever chemicals”, or substances that resist breaking down and persist in the body. Alarmingly, several additives used in plastics aren’t even required to be tested for safety by regulatory agencies. Currently, BPA and PFAS long-term effects are largely unknown to the public.

What Products Commonly Contain Microplastics?

Microplastics have been found in everyday items like salt, seafood, bottled water, milk, honey, sugar, beer, and even tea. Scientific methods for detecting these particles are still being standardized. Current data has yet to identify microplastic levels that pose a health risk. The lack of clarity in testing methods might overshadow the real scope of exposure to microplastics.

“Nature is really good at degrading nature. Nature is not so good at degrading man-made things” — Nylah McClain

Section 2: You Are What You Eat.

—Plastic included.

“A Person with Plastic Bits Pieces on Hand” by Alfo Medeiros from A Person with Plastic Bits Pieces on Hand is licensed under CC0

How Much Microplastic Do Humans Consume?

As you read this, you've probably already consumed around 285 microplastic particles (In theory). Clinging to many of those particles are chemical additives like PFAS that amplify the damage microplastics do to our bodies. PFAS are created to resist heat, water, and time itself. They don’t break down easily in the environment or the human body.

PFAS was first introduced in 1946 as a nonstick coating called Teflon, developed by DuPont. DuPont later partnered with 3M, a company formerly known as the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company, and is now modernly known as a multinational conglomerate. Made PFAS a key ingredient in countless consumer products. Today, it’s found in an overwhelming range of items we use and eat. Decades of widespread use have led to PFAS contaminating water, soil, and even the bloodstreams of both humans and animals. When paired with microplastics, this chemical forms a toxic duo. One is increasingly linked to serious health issues like:

- Cancer: Increased risk of cancers (prostate, kidney, testicular)

- Weight: Increased cholesterol levels and obesity

- Immune system: Reduced ability of the body's immune system to fight infections

- Reproductive system:

- Low birth weight: Weaker immune system, higher risk of chronic disease later in life

- Accelerated puberty: Disrupts normal hormonal development and can lead to long-term reproductive issues

- Behavioral changes: Connected to learning difficulties, anxiety, or attention disorders

- Changes in bone density: May weaken bones or affect proper skeletal development

But PFAS are only half the problem. The other half? Microplastics. Just as bad, maybe even worse. Alone, they’re already a problem. But mix them with additives like PFAS? You get a chemical time bomb, ticking away inside your body.

Health Effects of Microplastics in Humans

In recent studies, microplastics have been found inside the human lung tissue, where they can accumulate. Longer exposure to microplastics is thought to lead to diseases such as asthma and pneumoconiosis (a lung disease caused by inhaling dust).

Also, synthetic fibers that shed from clothing also float in the air, and some of these fibers are inhaled regularly. Experiments have also found that people who are exposed to microplastics can experience inflammation in the airway, causing symptoms like shortness of breath.

Once inside the body, microplastics and their toxic chemicals can irritate lung tissues and enter the bloodstream. These can lead to problems like asthma, pneumonia, allergic reactions, and damage to bronchial tissues. While simulations can predict where particles land, scientists can't fully comprehend how microplastics interact with lung mucus and cells.

Microplastics can also carry other toxic additives like Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs), which disrupt hormones, and heavy metals like lead and mercury. These particles in your body can lead to endocrine disruption, which can affect your:

- Growth - Energy, brain development, weight gain, and developmental issues in kids and babies.

- Stress response - How your body reacts to danger

- Reproductive system functions - Puberty, menstruation, fertility

Microplastics' small size allows them to bioaccumulate in important places. These include the blood-brain barrier, which protects your brain from harmful stuff (toxins, pathogens, etc.), your gut lining, where nutrients are stored, and the placenta. Even at birth, microplastics can accumulate in our bodies

It is theorized that microplastics can obstruct blood flow in capillaries, which could impact our brains. This can increase the likelihood of developing neurological diseases such as dementia.

So, now you know. Microplastics inhabit your body, and they're not going away anytime soon.

So what now?

Well, we need to talk about the human cost, of course, and why some communities are much more affected than others.

“Yes, I am finding that or I have found that the business is the hindering factor for my research specifically.” — Nylah McClain

Section 3: Am I Allowed To Write This?

There’s a reason why most of this information isn't mainstream.

"Baltimore smoke" by mikemccaffrey from https://www.flickr.com/photos/mccaffry/2923986728/ is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Environmental Justice & Microplastic Exposure

What if where you live determines how much poison you’re exposed to?

It’s 6:00 AM, Wednesday. Janice’s alarm wakes her up for school. The air in her room feels suffocating. She coughs weakly and sits up. As she changes into her clothes, she glances out the window. While some might expect a view of a park or a quiet backyard, all she sees is the silver power plant looming just a few buildings away.

She looks away, imagining the smoke stinging her eyes. Ever since the Baton Rouge Refinery went up, she and her friends have been getting sick. A track runner once known for her speed, she can’t keep up anymore.

Janice’s neighborhood is mostly low-income families, a mix of different races and cultures. Here in Louisiana, the area is called “Cancer Alley”. Not because they’re a threat to society, but because of the disproportionate rate of people at risk of having cancer in her area.

She laces up her shoes and walks to the bus. Smoke fills her eyes. She walks faster.

In many underrepresented communities like this one, people deal with the aftermath of having plastic plants right next to where they live. Baltimore is no different.

Baltimore’s largest trash-to-energy plant, operated by WIN Waste Innovations and located in South Baltimore, is one of the biggest sources of industrial air pollution in the city. It costs over 55 million dollars annually to treat the health consequences caused by its operation. Surrounding low-income marginalized neighborhoods like Cherry Hill, Mount Winans, Westport, Brooklyn, and Curtis Bay have experienced exposure to mercury, nitrogen oxides, and other toxic gases. Besides emitting toxic air gases, they also release plastic microplastics and PFAS into the environment. These plants are poisoning the air with things they claim are being turned into “energy”.

In Baltimore, 15% of Black residents live in neighborhoods ranked among the highest-risk for cancer-causing air pollution, in contrast to 7% of white residents. Therefore, Black residents are two times more likely to be living in areas with poor air quality. This is not by mistake, but by design. Decades of environmental racism have made sure of it, from silencing black, brown, and low-income voices to redlining. The government and big companies have made it extremely difficult for these underrepresented neighborhoods to speak out. They are forced to suffer in silence.

But the people are fighting back; Mayor Brandon M. and the City Council of Baltimore filed a lawsuit against several major plastic manufacturers (PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, etc.). They aim to prove that these mega-corporations created a public problem by contributing to plastic pollution and PFAS contamination. Breath Baltimore—a community-based research project that focuses on deploying air quality sensors in places that have reliable data—records this problem in real time. Allowing residents to see actual evidence of the dangerous spikes in pollution around their neighborhood, and push for policy change and cleaner solutions.

Why are billion-dollar companies allowed to poison people with no real consequences? Well, let's start from the beginning. When plastic was first created, regulations were extremely lax, letting companies put profit over people. For decades, corporations like DuPont and 3M hid evidence about the dangers of chemicals like PFAS, even as the risks started to become clearer. People have worked to install stricter laws, while marginalized communities have dealt with the brunt of the issue. This isn’t just a failure of policy or science; it’s an intentional choice to put profit before public health.

I know this situation sounds bleak, and honestly, it is. But here the truth is, nothing changes if we don’t fight for it. These systems in power right now were built to keep us tired, powerless, distracted, and uninformed. Because knowledge is power, and that power threatens their profit. But if you’re still here, still reading this, then you’ve already taken that first step. Awareness is where it starts. The more we learn, the more we understand, and it becomes much harder for corporations to hide under the shadows of vague labels and laws. We can’t fix what we understand, but when we do, we can organize, speak out, vote, protest–you name it. So you don’t need to be a scientist, but you do need to pay attention.

Section 4: There’s light at the end of the tunnel.

“Fight Today For A Better Tomorrow” by Markus Spiske from "Fight Today For A Better Tomorrow” is licensed under CC0

This topic is depressing to cover—and research too. Plastic pollution is something we, the public, are all familiar with but don’t really understand. However, the thing is, if we change the lens through which we look, the picture changes—and so can the future. Multiple initiatives like the Europe glass bottle program—focusing on collecting, sorting, and processing glass containers and other wastes to be used in new glass products—and major cleans led by the Ocean Clean Project. The largest cleanup in history, with a focus on removing plastics in the Pacific Ocean. Showing us that with the right perspective, we can get things done.

Works Cited

McClain, Nylah. Personal Interview. 2025.

“City of Baltimore Announces Lawsuit Filed Against Plastic Manufacturing.” Baltimore City Government, 20 June 2024, https://www.baltimorecity.gov/news/press-releases/2024-06-20-city-baltimore-announces-lawsuit-filed-against-plastic-manufacturing.

“South Baltimore Advocates File Civil Rights Complaint over Trash Incinerator Pollution Threats.” Environmental Integrity Project, https://environmentalintegrity.org/news/south-baltimore-advocates-file-civil-rights-complaint-over-trash-incinerator-pollution-threats/.

Wheeler, Timothy B. “Baltimore’s Water System Contains PFAS Chemicals at Levels above New EPA Health Advisory.” The Baltimore Sun, 24 June 2022, https://www.baltimoresun.com/2022/06/24/baltimores-water-system-contains-pfas-chemicals-at-levels-above-new-epa-health-advisory/.

“Microplastics Found in Human Brains.” UNM Health Sciences Center Newsroom, https://hscnews.unm.edu/news/hsc-newsroom-post-microplastics-human-brains.

“Baltimore.” Our America: Equity Report, https://ouramericaabc.com/equity-report/baltimore/environment.

“What Are Microplastics?” NOAA Ocean Service, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/microplastics.html.

Dawson, Maurice. “Microplastics in Drinking Water and Human Health.” ACS ES&T Water, 2024, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsestwater.4c00316.

“What Are Microplastics?” NOAA Marine Debris Program, https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/what-marine-debris/microplastics.

“Microbeads in Wastewater.” Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, https://portal.ct.gov/deep/municipal-wastewater/microbeads.

“What Is Plastic?” Worksheets Planet, https://www.worksheetsplanet.com/what-is-plastic/.

“Plastics Explained.” Plastics Europe, https://plasticseurope.org/plastics-explained/.

“The Age of Plastic: Parkesine to Pollution.” Science Museum, https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/chemistry/age-plastic-parkesine-pollution.

“How Do Microplastics Form?” CleanO2, https://cleano2.ca/blogs/journal/how-do-microplastics-form.

“Yale Experts Explain: Microplastics.” Yale Sustainability, https://sustainability.yale.edu/explainers/yale-experts-explain-microplastics.

“Microplastics Are Everywhere.” Harvard Medicine Magazine, https://magazine.hms.harvard.edu/articles/microplastics-everywhere.

“New Study Links Microplastics to Serious Health Harms in Humans.” Environmental Working Group, 2024, https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news/2024/03/new-study-links-microplastics-serious-health-harms-humans.

“Cumulative Exposure of Microplastics and Human Health.” National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10151227/.

“Toxicological Risk Assessment of Microplastics.” ScienceDirect, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0013935124004390.

“Microplastics and PFAS: The Connection.” Water Online, https://www.wateronline.com/doc/the-microplastics-and-pfas-connection-0001.

“Final Virtual PFAS Explainer.” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-10/final-virtual-pfas-explainer-508.pdf.

“Health Effects of PFAS.” Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/about/health-effects.html.

“What Are PFAS Chemicals?” Environmental Working Group, https://www.ewg.org/what-are-pfas-chemicals.

“Microplastics and Human Health Risks.” Science News, https://www.sciencenews.org/article/microplastics-human-bodies-health-risks.

“Microplastic Toxicity and the Human Body.” MDPI Foods, https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/12/18/3396.

“Australia’s Microplastic Waste Burden.” National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10826726/.

“Per‑ and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in the Environment.” ScienceDirect, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969719344468.

“PFAS: Forever Chemicals.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/technology/microplastic.

"Baton Rouge operations." ExxonMobil, ExxonMobil, https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/locations/united-states/baton-rouge-operations

Mashudi, Agung. "Plastic Bans Around the World." Solinatra, 14 Dec. [Year not specified], https://www.solinatra.com/news/plastic-bans-around-the-world

“Explained: What Are Nurdles?”

Fauna & Flora, 23 Sept. 2023,

www.fauna-flora.org/explained/explained-what-are-nurdles/.

O’Donoghue, Laura. “The Blood Brain Barrier: An Overview.” Assay Genie, 24

Mar. 2022, www.assaygenie.com/blog/the-blood-brain-barrier. Accessed 12 Aug. 2025.

How Does Pollution from BRESCO Affect Baltimore?

Bottle, Hello. “GLASS RECYCLING for BOTTLES in GERMANY.” Pearl Jars, 26 July 2023,

www.pearljars.com/en/blogs/blog/glass-recycling-for-bottles-in-germany.

Slat, Boyan. “The Ocean Cleanup.” The Ocean Cleanup, 2025, theoceancleanup.com/.