Airborne Toxic Metal Inhalation Higher in Communities of Color

Airborne Toxic Metal Inhalation Higher in Communities of Color

By Laura Quigley

A recent study in Nature Communications expands on what many Baltimore residents already know. We are living with environmental injustices in the city every day.

Not only are predominantly Black and Latino communities exposed to higher rates of air pollution, their residents also inhale far higher concentrations of airborne toxic metals than predominantly white communities. What that means: shorter life spans, more expensive health problems and difficulty breathing.

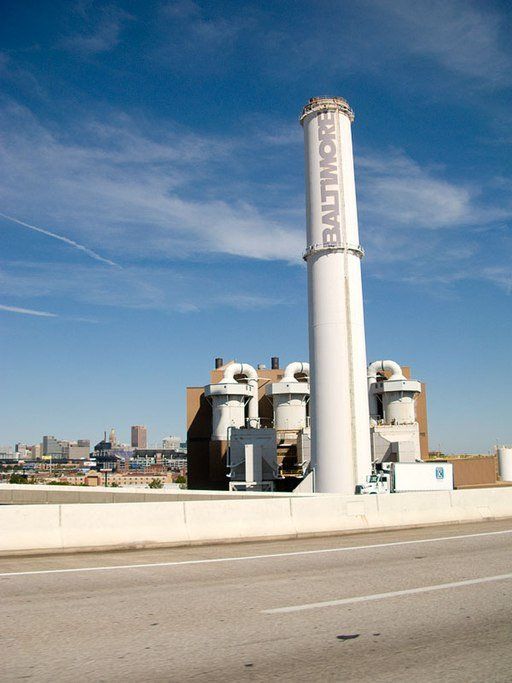

In Baltimore, residents in neighborhoods such as Westport and Curtis Bay live under the shadow of industries involved in manufacturing, incineration, and shipbuilding. The industries may or may not be there anymore – and many do not provide the jobs they once did – but the legacy pollution remains in many cases. And it harms the quality of life.

According to a study commissioned by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation in 2017, the nitrous oxide pollution from the Wheelabrator incinerator alone is responsible for $21 million in health and mortality costs in Maryland each year.

The recent toxic metal study shows that nitrous oxide pollution is not the only cause for concern.

According to an article published in The Washington Post, the study found that “in highly segregated counties, the average mass proportion of all fine-particulate metals associated with human-caused emissions was three to 12 times higher than in well-integrated ones.” Residents in predominantly Black and Latino communities are inhaling toxic metals, such as lead, nickel, copper, and zinc, in amounts far greater than their counterparts in communities that are racially integrated or primarily white.

How to change this disparity? Cleaning up pollution everywhere, of course, is the goal. But in particular, policymakers must look at the why of it all. Zoning laws, redlining, and other discriminatory practices have kept undesirable industries in certain parts of cities while banning them from other parts. The communities impacted most often don’t have a voice, either because of gerrymandering or lack of representation. Environmental justice means righting these wrongs through new policies that ensure everyone has the same rights to clean air and clean water. At least we’re talking about it now, and one step closer to maybe getting to a more equitable world.